I can’t say that I had the honor of making that acronym - that goes to Prof. Slocum - but I did have the honor of actually designing them.

FPGAs are bi-weekly assignments in 2.70 that involve building a contraption of our choice. The only restraint is that we we demonstrate some fundamental principle of engineering - and, of course, that we do the math.

FPGA 1: Finicky Preload with Great Applications

Have you ever counter-rotated two nuts to make a locknut? That question was rhetorical - everyone does that. But is it actually effective?

Our first FPGA was an attempt to quantify the actual strength of these preloaded “locknuts”. We first created an analytical model of two nuts held together.

(click to see code)

%% FPGA 1

%% parameters

E = 200 * 10^9; %steel 200 GPa

l = 1/20 * 0.0254; %lead = 1/20 in

L = 7/32*2 * 0.0254; %length of assemble (m)

u = 0.5; % coefficient of friction

r = 1/8 * 0.0254; %radius of bolt

%% derived parameters

A = (((7/16)/2)^2 *pi - ((1/4)/2)^2 *pi) * 0.0254^2; % m^2 front area of nut

%% Do calculation

f1 = @computeForce;

f2 = @computeTorque;

%% Function

% Put in equations form

function force = computeForce(original, final)

A = (((7/16)/2)^2 *pi - ((1/4)/2)^2 *pi) * 0.0254^2; % m^2 front area of nut

strain = ((final - original)/original)/2;

E = 190 * 10^9;

stress = strain*E;

force = stress * A;

end

function torque = computeTorque(preload)

u = 0.5;

r = 1/8 * 0.0254;

torque = preload*sind(75)*u*r;

end

We then put our tester-gadget into an Instron to see how our predictions lined up with reality. When using spring washers, our predictions were suprisingly accurate (within 22% in the worst trial) - but when directly mashing the nuts together, our model broke down. Our quest to fix this led to us realizing that bolt tensioning is a science within itself!

FPGA 2: Figure Pondering Grading of Assignment

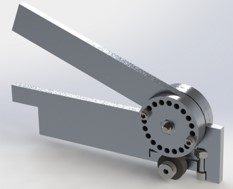

Our second FPGA was an attempt to make a bistable switch - but not just any switch. We wanted it to be the most satisfying switch in existence.

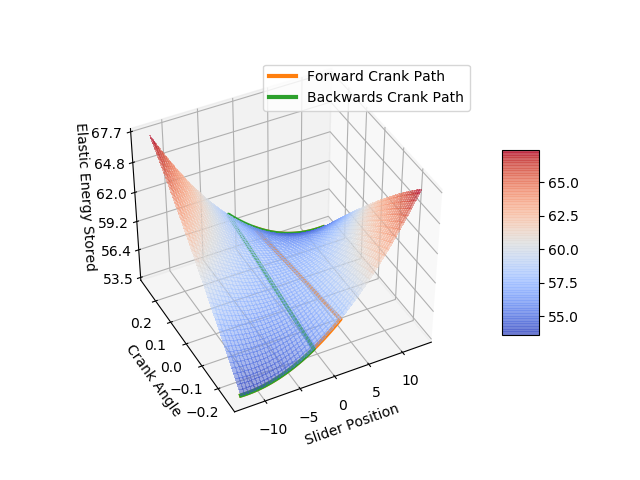

Our bistable switch features a special 2D arrangement of springs that allows it to snap between two positions with hysterises in a predictable fashion. The static behavior of the system was calculated using a potential energy well based solver.

(click to see code)

import numpy as np

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib import cm

from matplotlib.ticker import LinearLocator, FormatStrFormatter

# input parameters (all in mm | radians | N/mm)

p2s = 22 # pivot to slider distance

pl = 44 # pivot length

prom = np.pi / 6 # pivot range of motion (total)

lrom = 25 # slider range of motion (total)

ss = 44 # spring seperation

k = 1.3 / 30 # spring constant

srl = 30 # spring resting length

so = 15 # spring pivot seperation

precision = 100 # number of points to evaluate

# equation derived from matlab

def energy(pa, delta):

"""

equation source:

pc = [-pl*np.np.cos(pa), pl*np.np.sin(pa)] % pivot attachment point coords

tpc = [p2s, ss/2 + delta] % top spring attachment coords

bpc = [p2s, -ss/2 + delta] % bottom spring attachment coords

tsl = norm(pc - tpc) % top spring length

bsl = norm(pc - bpc) % bottom spring length

tse = (tsl - srl)*k % top spring energy

bse = (bsl - srl)*k % bottom spring energy

te = tse + bse % total energy

matlabs symbolic stuff is way easier lol

delta -> shift in spring origin

pa -> angle of pivot

"""

return (k*(srl - (abs(delta - ss/2 + so*np.cos(pa) - pl*np.sin(pa))**2 + abs(p2s + pl*np.cos(pa) + so*np.sin(pa))**2)**(1/2))**2)/2 + (k*(srl - (abs(delta + ss/2 - so*np.cos(pa) - pl*np.sin(pa))**2 + abs(p2s + pl*np.cos(pa) - so*np.sin(pa))**2)**(1/2))**2)/2

# create map of energy

energy_map_func = np.vectorize(energy)

deltas = np.linspace(-lrom / 2, lrom / 2, precision)

pas = np.linspace(-prom / 2, prom / 2, precision)

pas_Y, deltas_X = np.meshgrid(pas, deltas)

energies = energy_map_func(pas_Y, deltas_X)

# map forward stroke

# starting energy

def generate_path(flipped):

angles_indexes = [energies[0].argmin()]

if flipped:

angles_indexes = [energies[energies.shape[0] - 1].argmin()]

steps = range(1, energies.shape[0])

if flipped:

steps = reversed(steps)

for i in steps:

c_angle = angles_indexes[-1]

while (c_angle > 0):

if energies[i][c_angle] > energies[i][c_angle - 1]:

c_angle = c_angle - 1

else:

break

while (c_angle < len(energies[i]) - 1):

if energies[i][c_angle] > energies[i][c_angle + 1]:

c_angle = c_angle + 1

else:

break

angles_indexes.append(c_angle)

path_deltas = deltas

if flipped:

path_deltas = [i for i in reversed(deltas)]

path_pas = [pas[i] for i in angles_indexes]

path_energies = [energies[i][j]

for i, j in zip(range(precision), angles_indexes)]

if flipped:

path_energies = [energies[i][j] for i, j in zip(

reversed(range(precision)), angles_indexes)]

return (path_deltas, path_pas, path_energies)

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.gca(projection='3d')

# Plot the surface.

surf = ax.plot_surface(deltas_X, pas_Y, energies, alpha=0.5,

cmap=cm.coolwarm, linewidth=0, antialiased=False)

line_forward = ax.plot(*generate_path(False), linewidth=3, label="Forward Crank Path")

line_backward = ax.plot(*generate_path(True), linewidth=3, label="Backwards Crank Path")

# Customize the z axis.

ax.zaxis.set_major_locator(LinearLocator(6))

ax.zaxis.set_major_formatter(FormatStrFormatter('%.01f'))

ax.set_xlabel("Slider Position")

ax.set_ylabel("Crank Angle")

ax.set_zlabel("Elastic Energy Stored")

ax.legend()

# Add a color bar which maps values to colors.

fig.colorbar(surf, shrink=0.5, aspect=5)

plt.show()

This gave us a nice idea of how the switch would move over its range of motion. The final test showed that our model had only 16% error - most of which came from errors in measuring the resting length of our springs.

FPGA 3: Flexures Put in Ghastly Applications

Flexures are wonderful, but they’re not always easy to make. Their very nature means that they tend to move around as you machine them. Most people solve this by simply…not machining them. But what if you did?

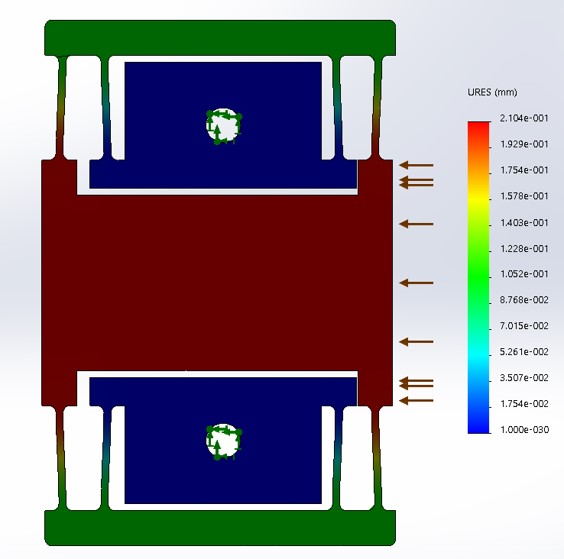

For this FPGA, we tried to quantify how bad tolerances would be if you tried to machine a pocket in a folded-stage flexure. A lot of tuning was needed to get the damn thing to cut in the first place. A lot of punishment was taken every time we messed up :c

Our final model predicted our tolerances to be off by 0.08mm - and our final measurements confirmed this to be accurate (although our measurement techniques could surely be improved).

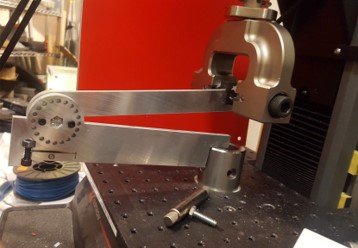

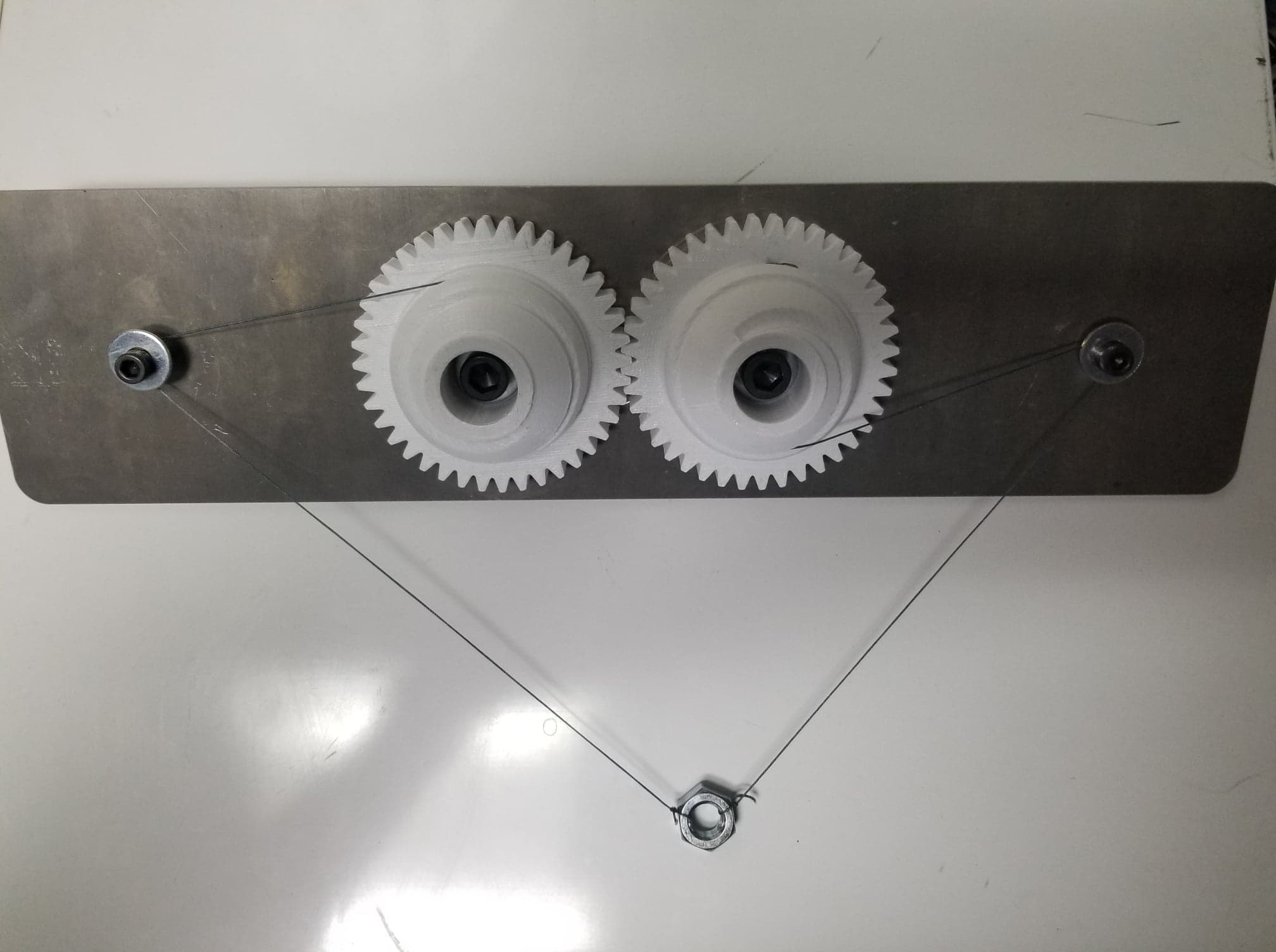

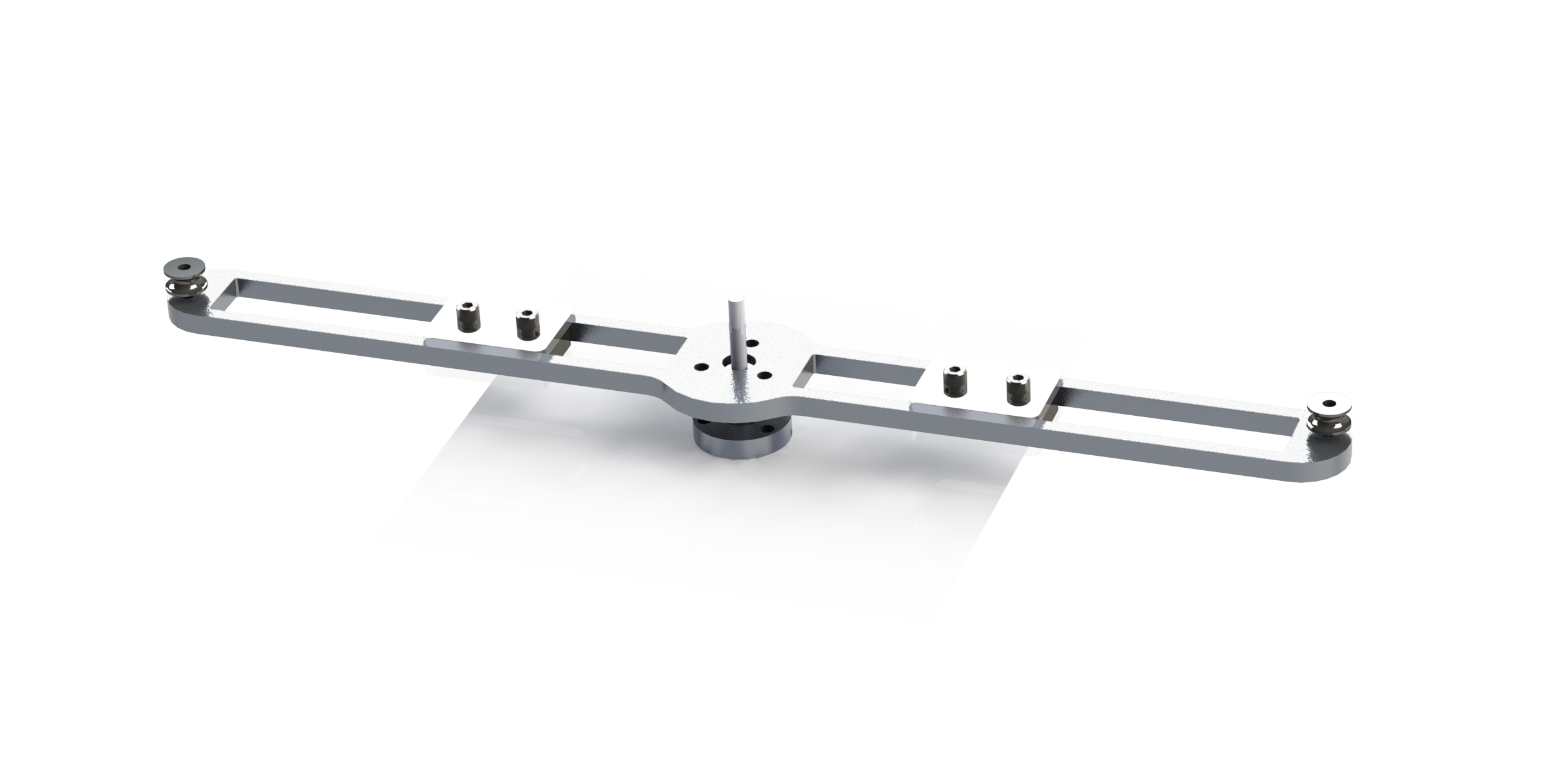

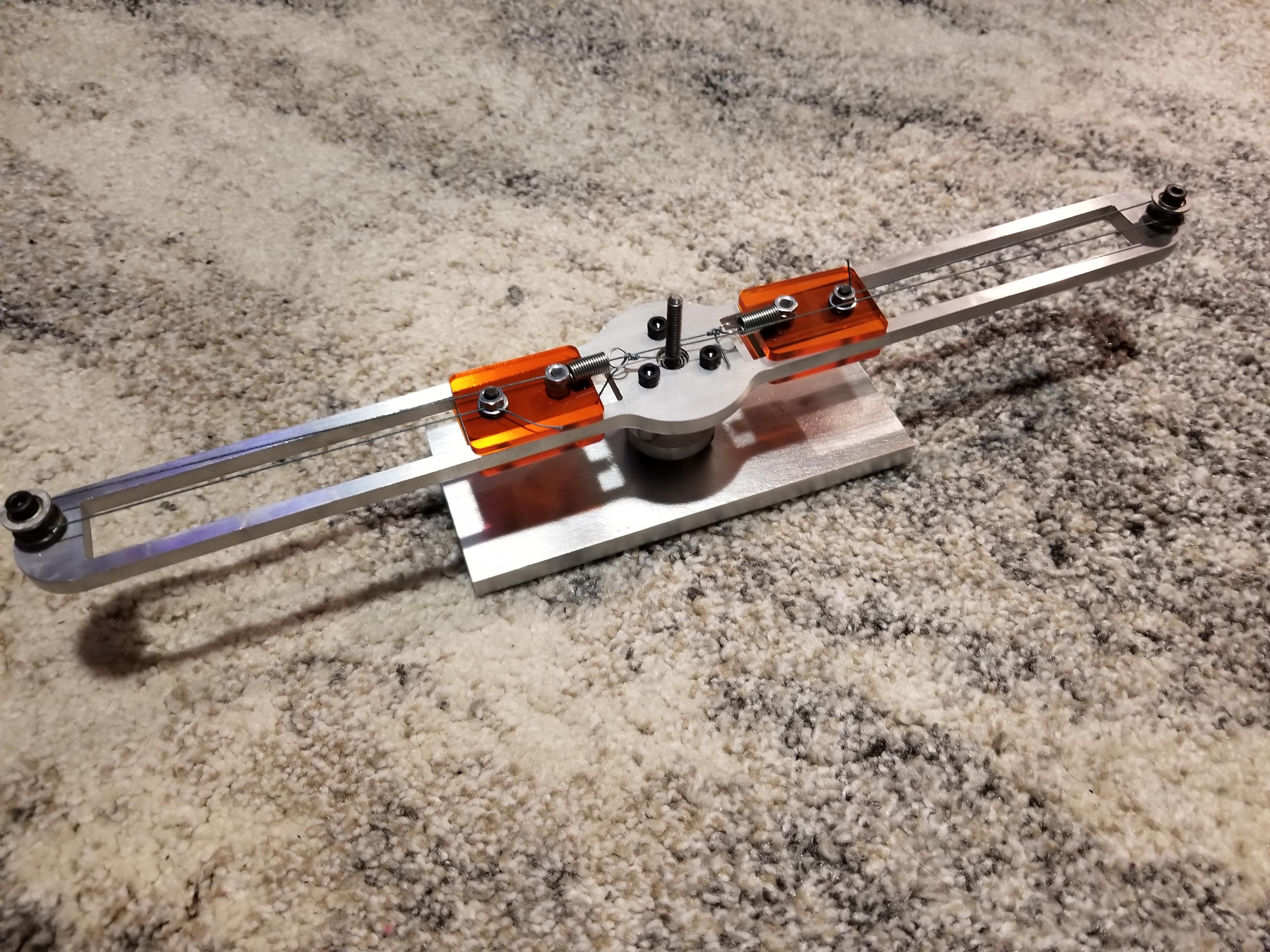

FPGA 4: Freaky Pulleys Going Axially

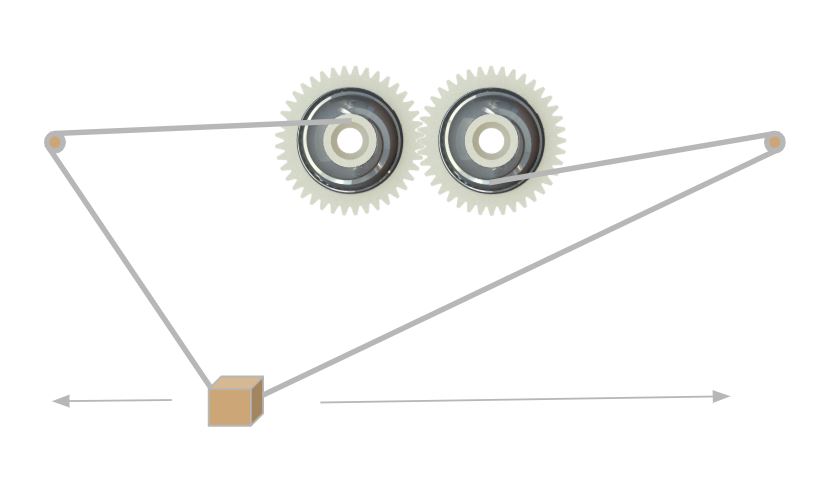

Overhead cranes typically use large steel I-beams upon which steel rollers glide. Why not make it more like a zipline? Well, that would just result in the rope sagging. Why not use rope sagging to your advantage?

The basic concept was to have two nonlinear winches synchronized together by gears. When one winch releases rope, the other winch takes up rope at the exact rate needed to keep a hanging object moving along a straight line. Tricky, but possible.

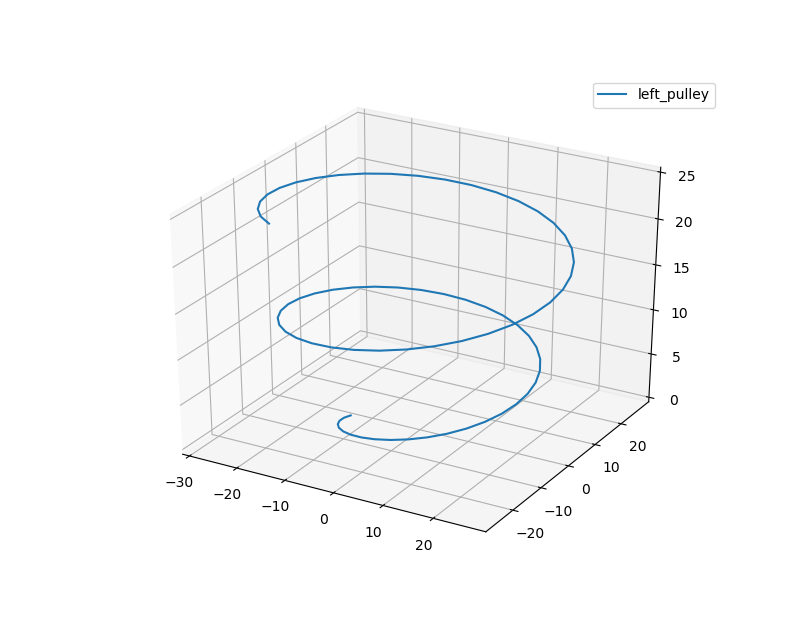

A giant pile of python code and math was used to generate a parametric path through space that represented the shape of the winch.

(click to see code)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

# input parameters

a = 15 # ratio of pulley angle (radians) to x distance traveled (mm)

H = 100 # distance between pulley and object (mm)

W = 300 # distance between pulleys (mm)

x_padding = 50 # padding between x travel and pulley spacing (mm)

pulley_height = 25 # width of pulley (mm)

# resolution

num_points = 75

# derived figures

x_min = x_padding

x_max = W - x_padding

xs = np.linspace(x_min, x_max, num_points)

thetas = xs / a

pitch = pulley_height / (thetas[-1] - thetas[0])

ds = np.sqrt(np.square(2 * xs * a) / (np.square(xs) + np.square(H)) - np.square(pitch))

# exporting to solidworks curve format

p_x_left = np.cos(thetas) * ds

p_x_right = -np.cos(thetas) * ds

p_y_left = np.sin(thetas) * ds

p_y_right = np.sin(thetas) * ds

p_z_left = np.linspace(0, pulley_height, num_points)

p_z_right = np.linspace(pulley_height, 0, num_points)

# previewing helix shape

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.gca(projection='3d')

ax.plot(p_x_left, p_y_left, p_z_left, label='left_pulley')

# ax.plot(p_x_right, p_y_right, p_z_right, label='right_pulley')

ax.legend()

plt.show()

# saving path to file

with open('output_left.sldcrv', 'w') as file:

output = '\n'.join(' '.join((str(x), str(y), str(z)))

for x, y, z in np.vstack((p_x_left, p_y_left, p_z_left)).T)

file.write(output)

with open('output_right.sldcrv', 'w') as file:

output = '\n'.join(' '.join((str(x), str(y), str(z)))

for x, y, z in np.vstack((p_x_right, p_y_right, p_z_right)).T)

file.write(output)

The final pulley system - despite all of our expectations - somehow worked as expected! Only a few nonlinearities were observed (mostly due to improper assembly).

FPGA 5: Figure Pulling Great mAss

When hit, a tetherball initially starts wrapping around the poll slowly but speeds up as it winds inwards. This is due to a decreasing moment of inertia and conserved energy. What would a flywheel built to mimick this look like?

A small arm with two counterbalanced weights spins on a pivot. The spinning of the arm causes the two weights to be simultaneously winched together. Predicting how the speed would change as a result was suprisingly difficult and required my partner to write a custom Euler-Lagrange simulator.

(click to see code)

function simulate_leg()

%% Definte fixed paramters (obtained from CAD)

m1 =.02 + .210; m2 =.0225;

m3 = .004; m4 = .017;

I1 = 45.389 * 10^-6; I2 = 22.918 * 10^-6;

I3 = 3.2570 * 10^-6; I4 = 22.176 * 10^-6;

l_OA=.011; l_OB=.042;

l_AC=.096; l_DE=.096;

l_O_m1=0.0364; l_B_m2=0.040;

l_A_m3=1/2 * l_AC; l_C_m4=1/2 * (l_DE+ l_OB-l_OA);

g = 9.81;

%% Parameter vector

p = [m1 m2 m3 m4 I1 I2 I3 I4 l_O_m1 l_B_m2 l_A_m3 l_C_m4 l_OA l_OB l_AC l_DE g]';

%% Perform Dynamic simulation

tspan = [0 2];

z0 = [-pi/4; pi/2; 0; 0];

opts = odeset('AbsTol',1e-8,'RelTol',1e-6);

sol = ode45(@dynamics,tspan,z0,opts,p);

%% Compute Energy

E = energy_leg(sol.y,p);

figure(1); clf

plot(sol.x,E);xlabel('Time (s)'); ylabel('Energy (J)');

%% Compute foot position over time

rE = zeros(2,length(sol.x));

for i = 1:length(sol.x)

rE(:,i) = position_foot(sol.y(:,i),p);

end

w =100;

% Plot desired and actuatl foot trajectories

figure(2); clf;

plot(sol.x,rE(1,:),'r','LineWidth',2)

hold on

plot(sol.x,0.025 * cos(w*sol.x) ,'r--');

plot(sol.x,rE(2,:),'b','LineWidth',2)

plot(sol.x,-.125+0.025*sin(w*sol.x) ,'b--');

xlabel('Time (s)'); ylabel('Position (m)'); legend({'x','x_d','y','y_d'});

%% Animate Solution

figure(3); clf;

hold on

%% Optional, plot foot target information

% Target traj. Q 1.6

plot( .025*cos(0:.01:2*pi), -.125+.025*sin(0:.01:2*pi),'k--');

animateSol(sol,p);

end

function tau = control_law(t,z,p)

% Controller gains, Update as necessary for Problem 1

K_x = 40; % Spring stiffness X

K_y = 40; % Spring stiffness Y

D_x = 4; % Damping X

D_y = 4; % Damping Y

% Desired position of foot is a circle

w = 30;

rEd = [0 -.125 0]' + .025*[cos(w*t) sin(w*t) 0]'; % Desired position of foot

vEd = .025*[-sin(w*t)*w cos(w*t)*w 0]'; % Desired velocity of foot

rE = position_foot(z,p);

vE = velocity_foot(z,p);

J = jacobian_foot(z,p);

% Compute virtual foce

f = [K_x * (rEd(1) - rE(1) ) - D_x * (vE(1) - vEd(1) ) ;

K_y * (rEd(2) - rE(2) ) - D_y * (vE(2) - vEd(2) ) ];

% Map to joint torques

tau = J' * f;

end

function tau = control_law_extended(t,z,p)

% Controller gains, Update as necessary for Problem 1

K_x = 40; % Spring stiffness X

K_y = 40; % Spring stiffness Y

D_x = 4; % Damping X

D_y = 4; % Damping Y

% Desired position of foot is a circle

w = 100;

rEd = [0 -.125 0]' + .025*[cos(w*t) sin(w*t) 0]'; % Desired position of foot

vEd = .025*[-sin(w*t)*w cos(w*t)*w 0]'; % Desired velocity of foot

aEd = [-.025*w^2*cos(t*w) -.025*w^2*sin(w*t)]';

rE = position_foot(z,p);

vE = velocity_foot(z,p);

J = jacobian_foot(z,p);

dJ = jacobian_dot_foot(z,p);

%Compute dynamic coefficients

M = A_leg(z,p);

lambda = inv(J')*M*inv(J);

V = Corr_leg(z,p);

mu = inv(J')*V-lambda*dJ*z(3:4);

G = Grav_leg(z,p);

rho = inv(J')*G;

% Compute virtual foce

f = [K_x * (rEd(1) - rE(1) ) - D_x * (vE(1) - vEd(1) ) ;

K_y * (rEd(2) - rE(2) ) - D_y * (vE(2) - vEd(2) ) ];

f_new = f + lambda*aEd + rho;

% Map to joint torques

tau = J' * f_new;

end

function dz = dynamics(t,z,p)

% Get mass matrix

A = A_leg(z,p);

% Compute Controls

tau = control_law_extended(t,z,p);

% Get b = Q - V(q,qd) - G(q)

b = b_leg(z,tau,p);

% Solve for qdd.

qdd = A\b;

dz = 0*z;

% Form dz

dz(1:2) = z(3:4);

dz(3:4) = qdd;

end

function animateSol(sol,p)

% Prepare plot handles

hold on

h_OB = plot([0],[0],'LineWidth',2);

h_AC = plot([0],[0],'LineWidth',2);

h_BD = plot([0],[0],'LineWidth',2);

h_CE = plot([0],[0],'LineWidth',2);

xlabel('x'); ylabel('y');

h_title = title('t=0.0s');

axis equal

axis([-.2 .2 -.3 .1]);

%Step through and update animation

for t = 0:.01:sol.x(end)

% interpolate to get state at current time.

z = interp1(sol.x',sol.y',t)';

keypoints = keypoints_leg(z,p);

rA = keypoints(:,1); % Vector to base of cart

rB = keypoints(:,2);

rC = keypoints(:,3); % Vector to tip of pendulum

rD = keypoints(:,4);

rE = keypoints(:,5);

set(h_title,'String', sprintf('t=%.2f',t) ); % update title

set(h_OB,'XData',[0 rB(1)]);

set(h_OB,'YData',[0 rB(2)]);

set(h_AC,'XData',[rA(1) rC(1)]);

set(h_AC,'YData',[rA(2) rC(2)]);

set(h_BD,'XData',[rB(1) rD(1)]);

set(h_BD,'YData',[rB(2) rD(2)]);

set(h_CE,'XData',[rC(1) rE(1)]);

set(h_CE,'YData',[rC(2) rE(2)]);

pause(.01)

end

end

Once it was built, we used Tracker to see whether our observations matched up with our predictions. Parasitic frictional losses ended up thwarting our model… but we could still clearly see the device speeding up over time!

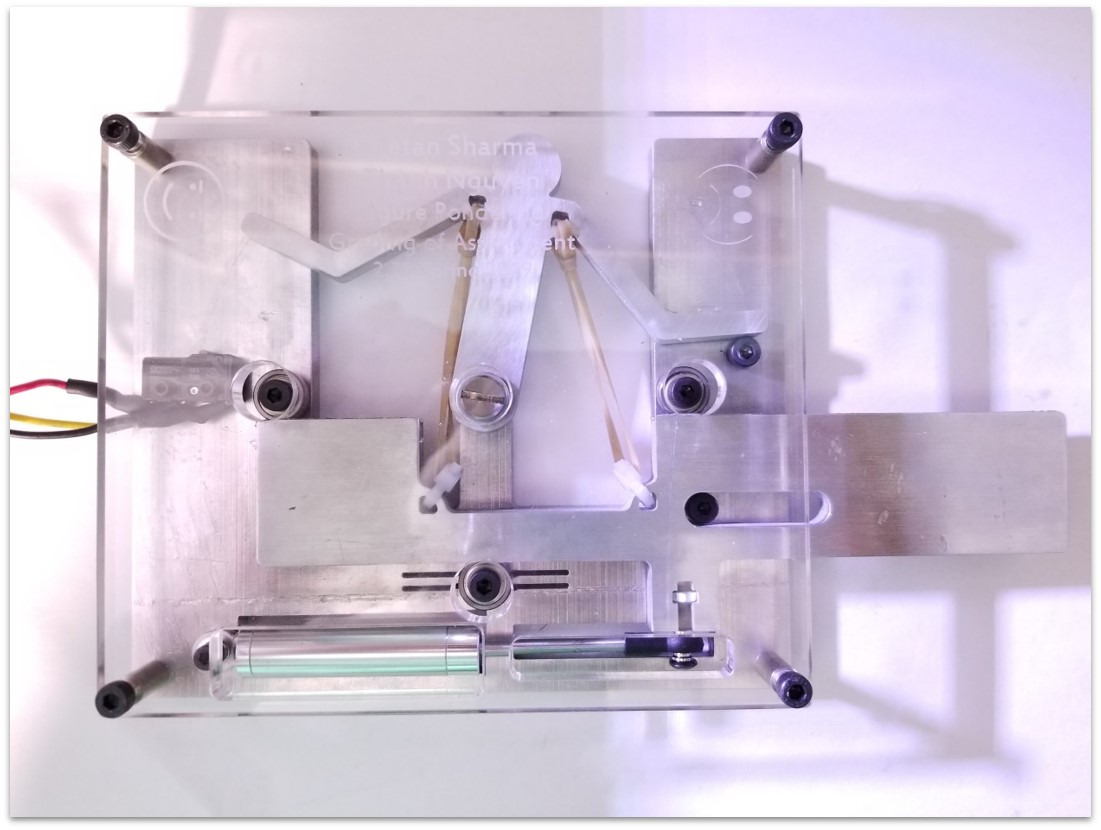

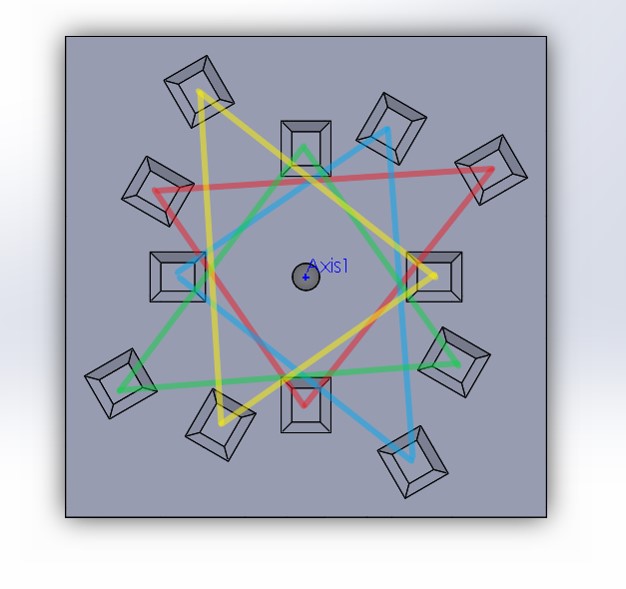

FPGA 6: Fixturing for Precise Gadget Alignment

Kinematic couplings are great for creating repeatable fixtures, but things get weird when you try to have multiple orientations. Undercontrained/overcontrained/undesired orientations crop up when you try to place multiple KCs around one axis. How do you get around this?

If the coupler locations are offset properly, you can get a coupler that locks in place at an arbitrary number of locations (with no invalid configurations!)

We predicted that there would be some amount of angular error in our coupler (specifically, a max deviation of 1.61e-7 m). We tried testing this using a laser pointer mounted to the top and aimed down a 127ft hallway…

…and we couldn’t measure anything! We believe that the brinelling of the KC grooves might have made this more repeatable than we originally thought!