Last year, I was fortunate enough to join the Center for Bits and Atoms at MIT as a Masters student. The CBA deals with an assortment of cool topics; the niche I chose to dive into was personal fabrication.

(The full project can be found here along with the actual thesis)

CNC mills are by and large my favorite machines. I built my first CNC router back in high school out of MDF scraps and eBay bearings. It wasn’t pretty, but it let me make things I never thought I’d be able to make. I was immediately an addict; one of the first things I built was a second CNC router.

Like any CNC operator, I broke a lot of endmills. But after many years of using these machines, I am proud to say that… I still break endmills. What gives?

Machining Parameter Selection is Tricky

Machining with a flat endmill is an incredibly complex process. A complex mixture of thermal, tribological, static, and dynamic mechanisms govern cutting forces. Models that describe cutting are equally complex and rely on empirically determined constants; for this reason, most machinists resort to “playing by ear” (usually in a literal sense).

One then has to wonder: is there a way of abstracting out all of these complexities? Can the machine figure out feeds and speeds by itself with no user input?

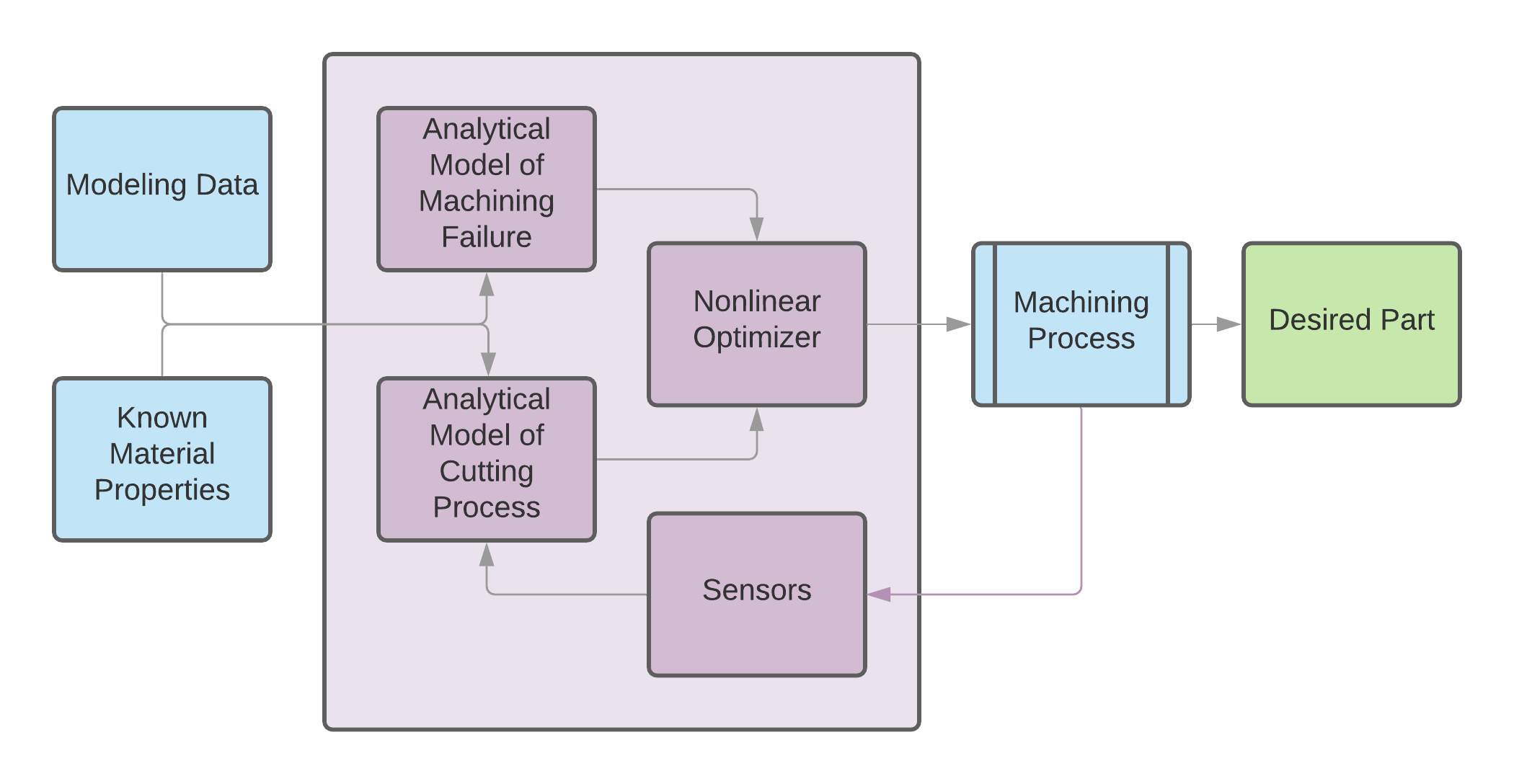

Intelligent Controllers

In a nutshell: my thesis project was to create an intelligent CNC controller that would use low-cost spindle torque and tool force sensors to fit a model describing cutting forces. The controller would then use this model and a numerical optimizer to find feeds and speeds that would maximize thoroughput and minimize deflection / tool breakage.

I won’t try to fit my whole thesis in this post, but I will share some highlights from the finished project.

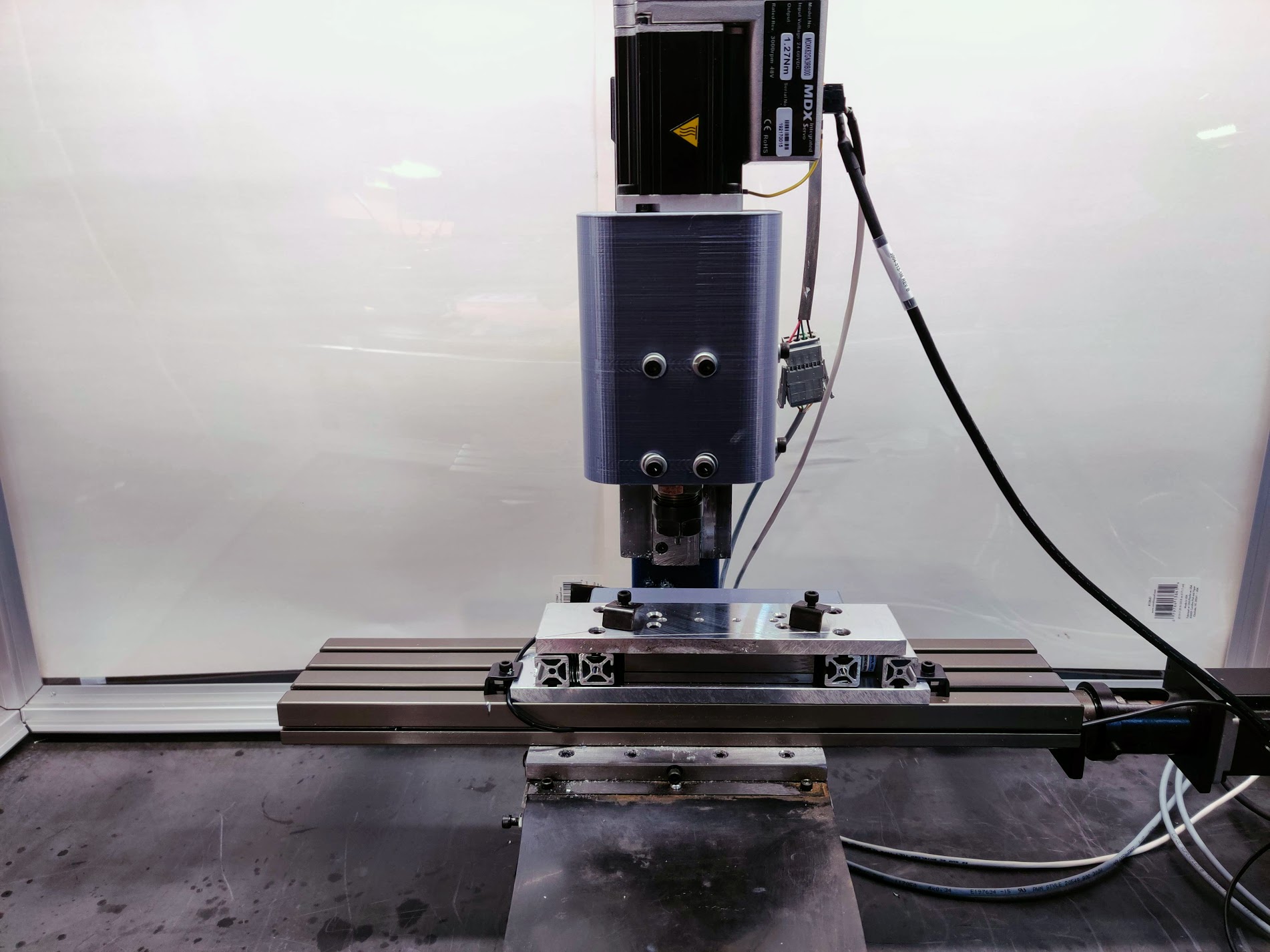

Most of this thesis was completed during the COVID-19 pandemic in a small garage in North Carolina. I didn’t have access to my lab space, so I had to make do with the tools I had. A retrofitted Taig CNC micro mill was the proverbial guinea pig for this project. The machine itself was generously donated to my lab by Ted Hall from ShopBot.

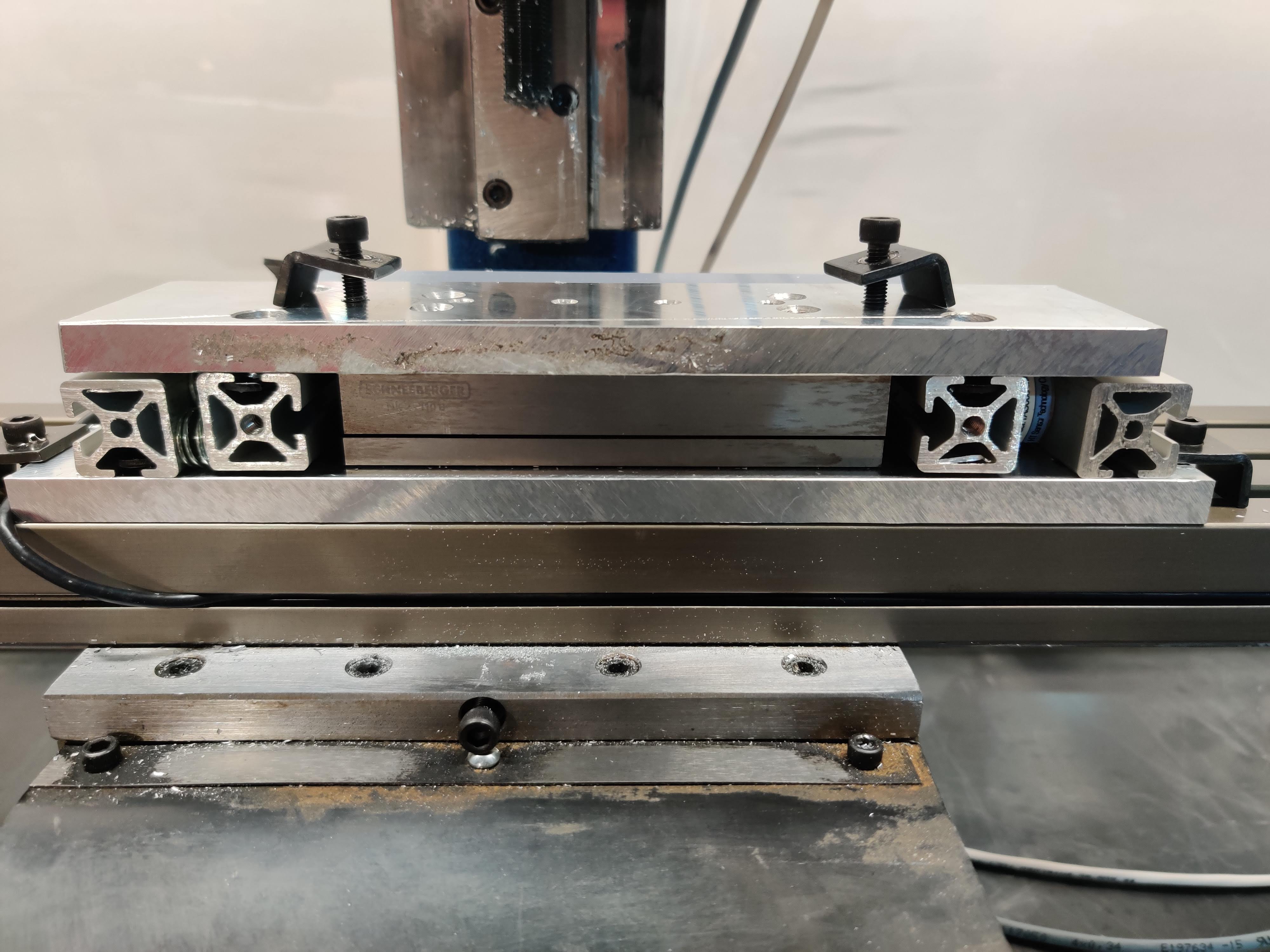

A uniaxial tool-force dynamometer was built to gather tool force readings. Spindle currents were used to infer spindle torques.

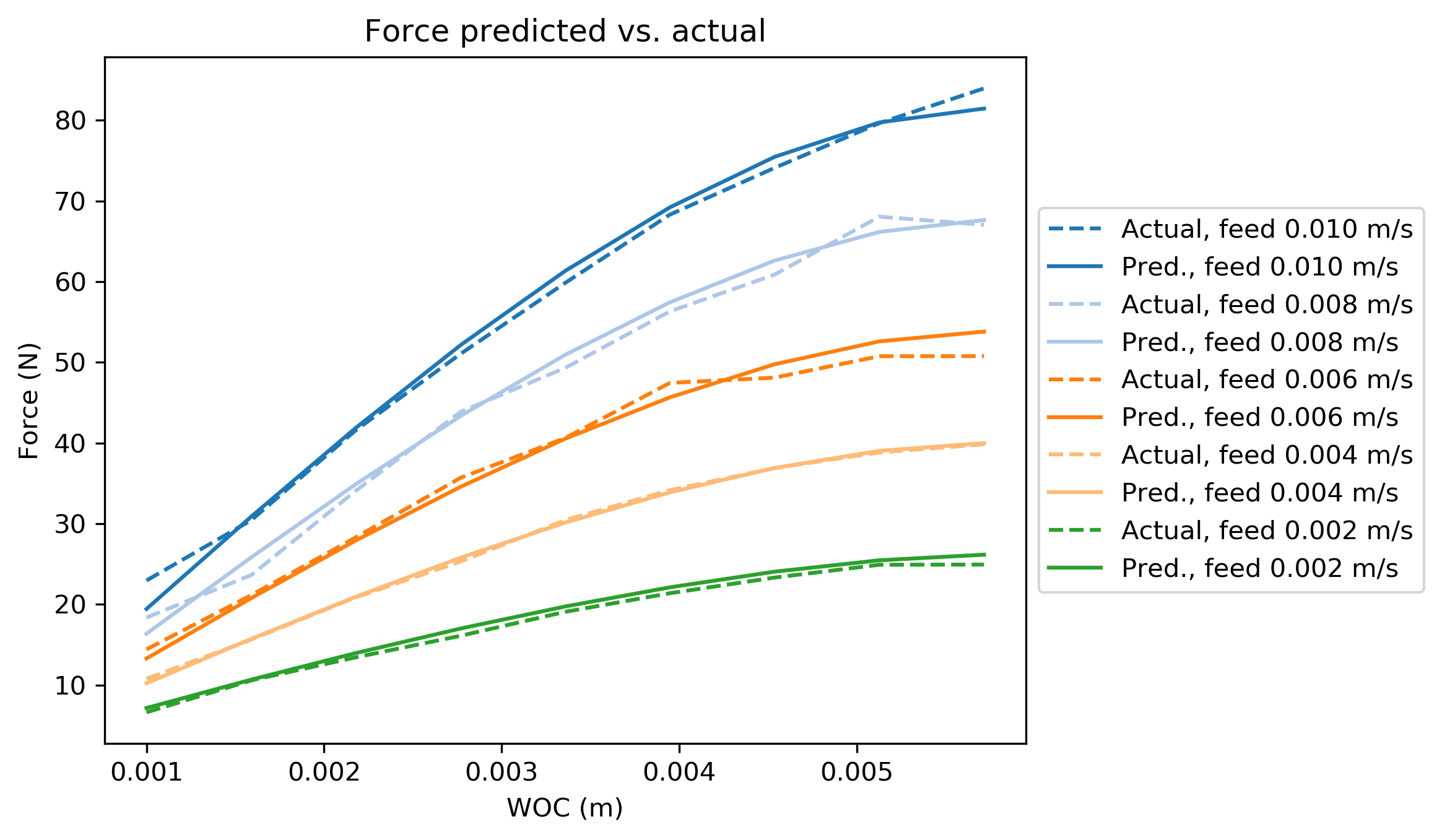

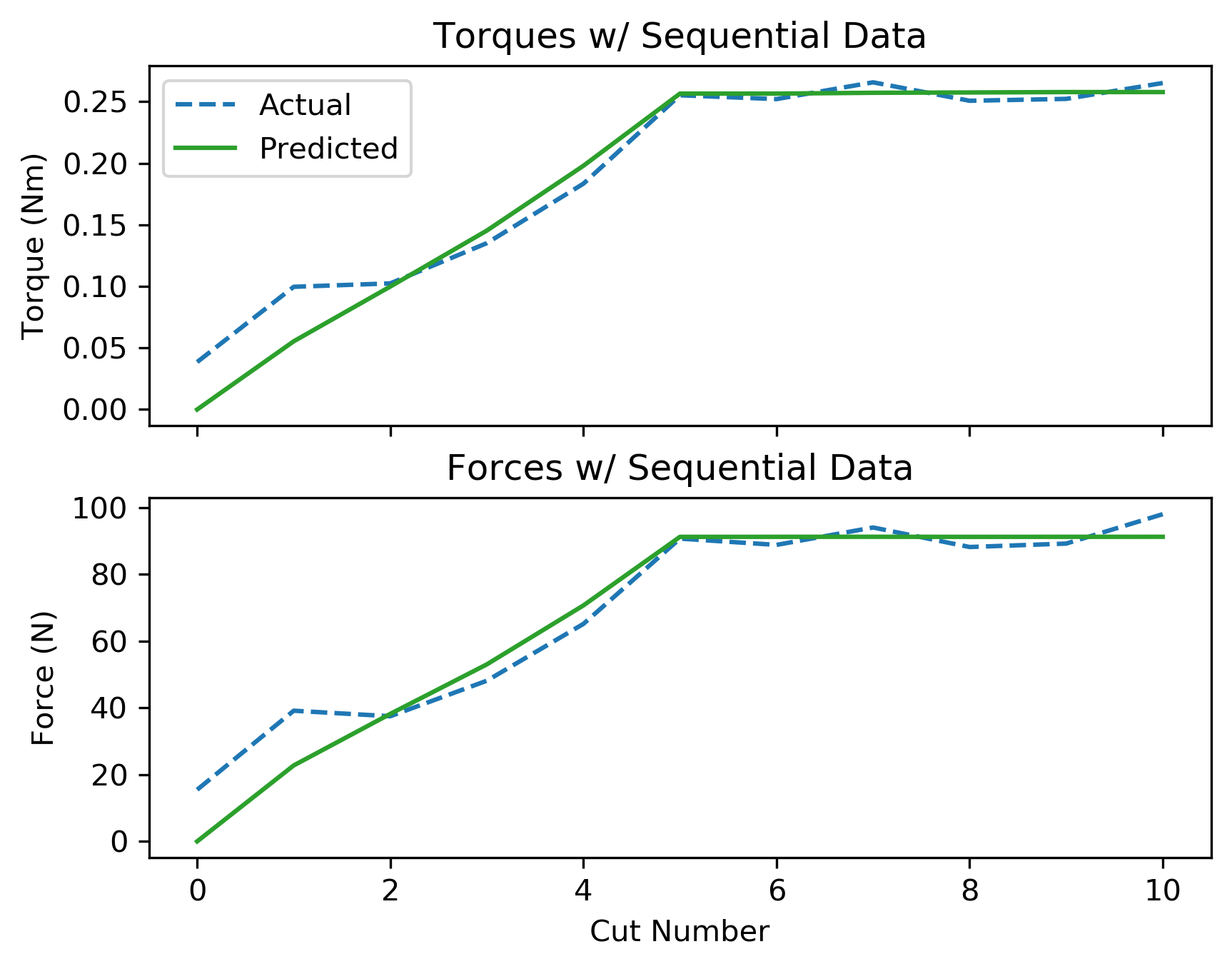

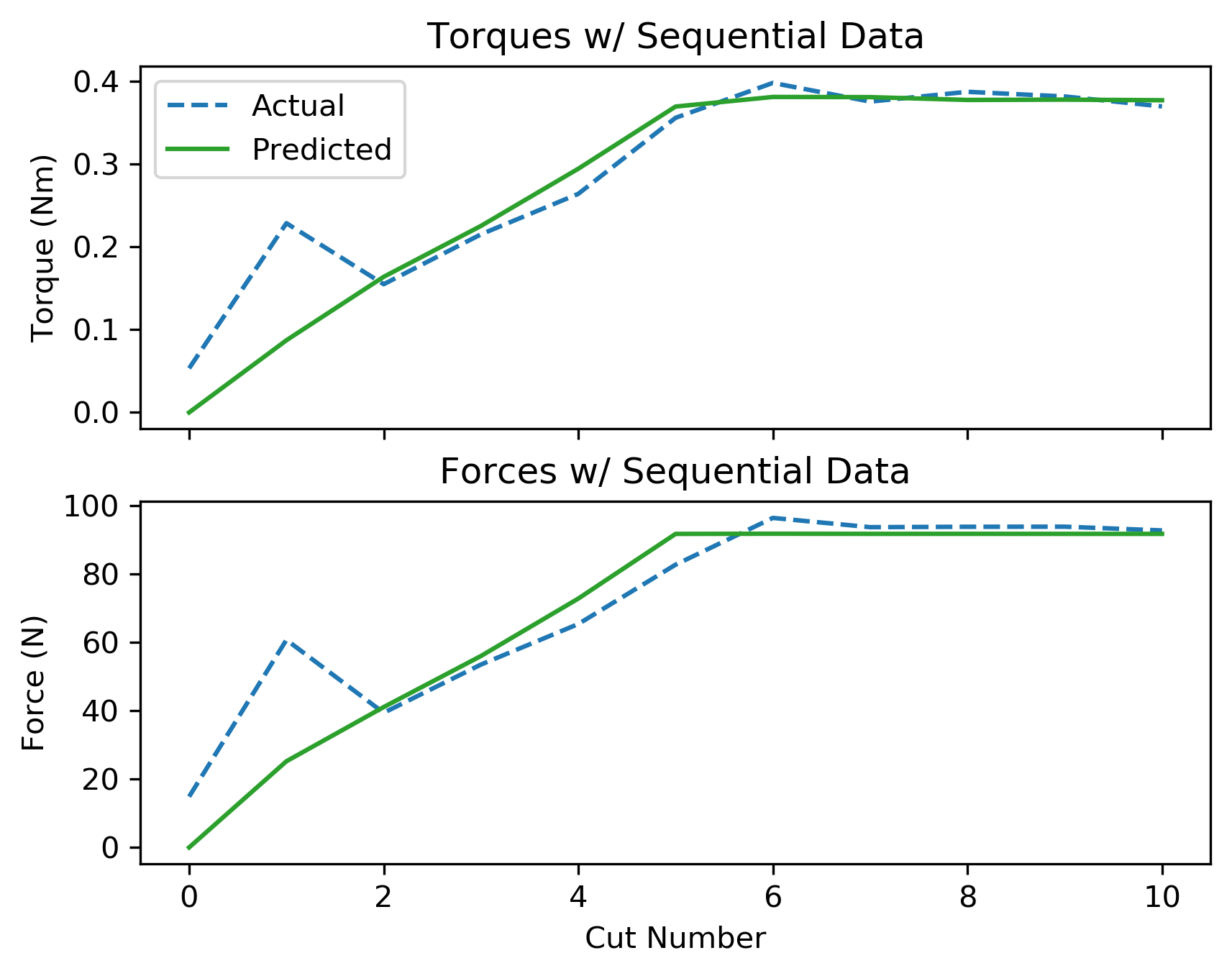

These readings were used to estimate the coefficients for a quasi-linear cutting force model in real time. The model worked incredibly well!

This model was simultaneously used alongside a Weibull-based endmill failure model to find optimal feeds and speeds. Future cut data would be used to improve the accuracy of the model.

To prove that the system could handle any material, I let it loose on materials that were both easy to machine and horrible to machine. The graphs above show the machine converging on optimal cut parameters for 6061 aluminum and 304 stainless steel while simultaneously building an accurate model of the forces involved.

Watching a tiny Taig mill “hogging” stainless steel with no supervision was pretty incredible to watch!

This thesis was a blast to work on - I never thought I’d get a degree from playing around with CNC machines! I’m hoping to work on this more in the future; I’d love to see this turn into a proper open-source project one day.